We Can Hack Pain — But Should We?

The Opioid Crisis, Soylent, and Retaining Humanity

Red opium poppy plants. Photo by Marten Bjork on Unsplash

I learned recently that Americans are the highest opioid users per capita in the world. That was no surprise. However, this next fact made me stop and think: there is no evidence that Americans experience any more pain than people from other countries.

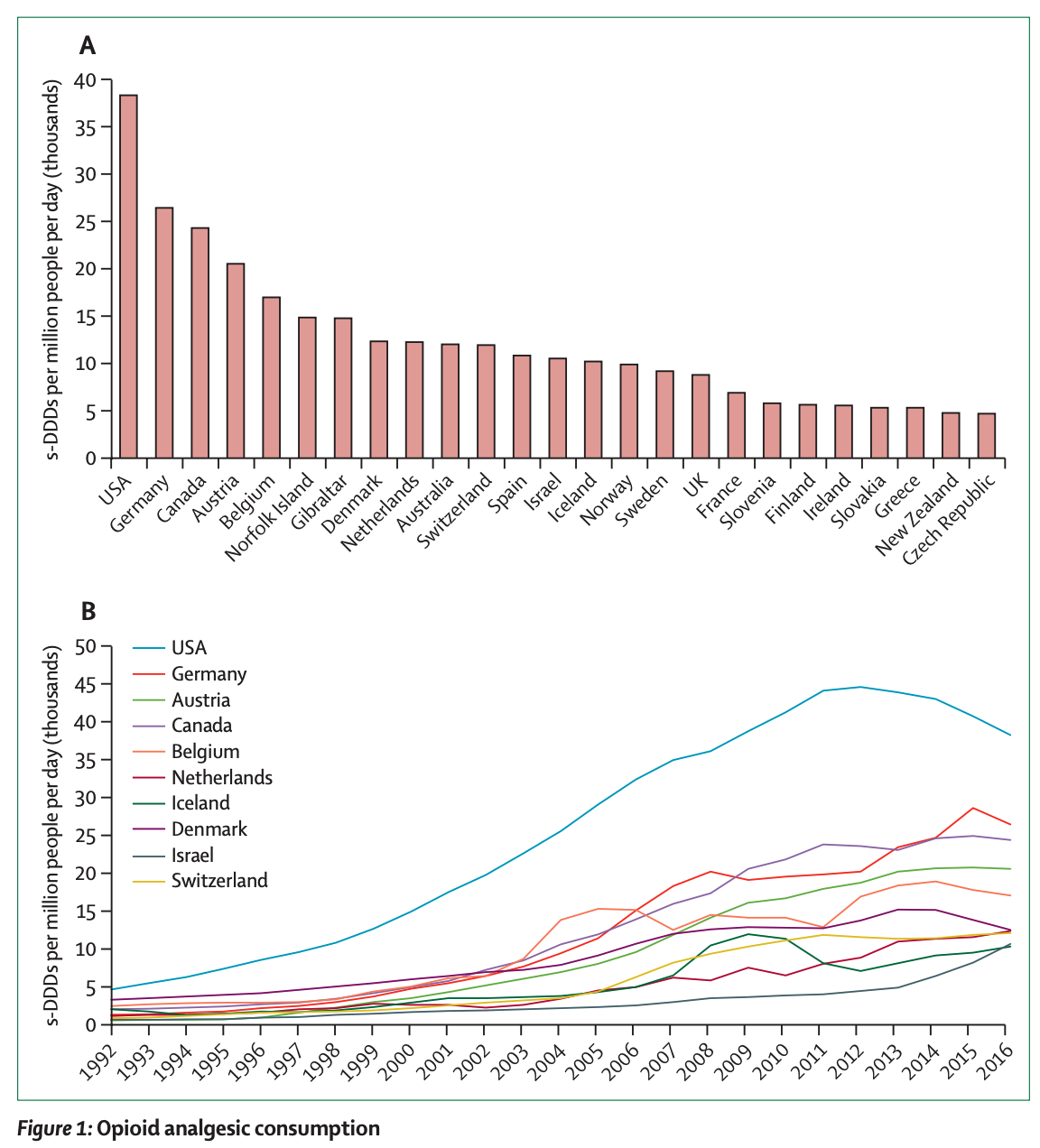

A 2019 Lancet study found that the use of opioid analgesics (painkillers) in the USA far exceeds its use in other nations. The US population consumed 68% of the world’s prescribed opioids between 2011 and 2013, despite only making up 4.25% of the global population. What’s going on?

s-DDDs=standardised defined daily doses, or the average dose of opioid per day. The USA leads the pack in both opioid usage and the growth of usage in the last few decades. Degenhardt et al., 2019

Origins of the Opioid Crisis

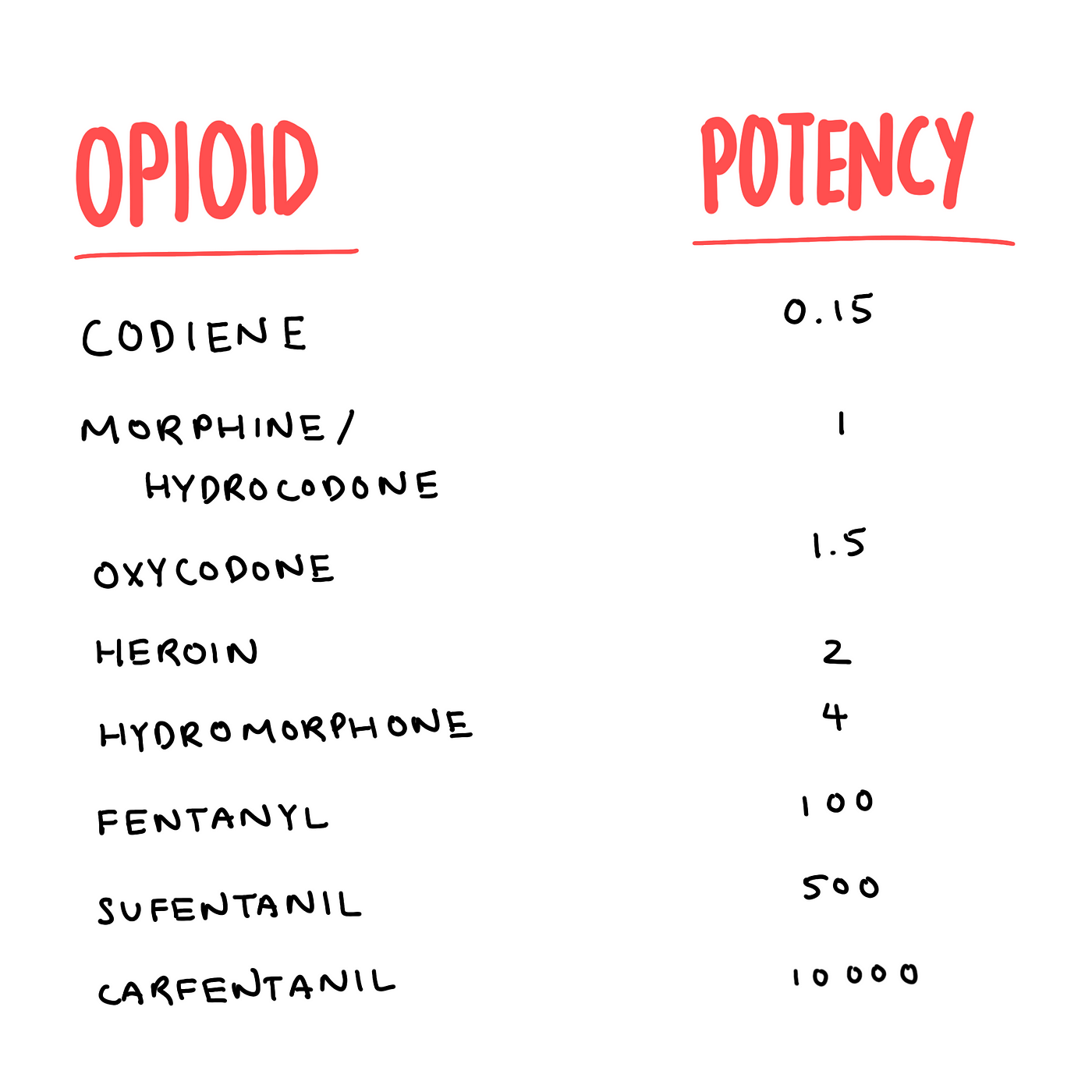

Morphine, the original opioid, is isolated from the opium poppy plant and has been used for millennia in the middle eastern societies by ancient priests and physicians. Today, we have developed synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and carfentanil, which are 100 and 10 000 times more potent than morphine respectively. Opioid drugs are listed by the World Health Organization as an essential medicine, indicated for the treatment of acute pain, pain caused by cancer, and palliative care.

Relative potencies of opioids. Image by Author. Data: CDC.

However, in North America, many patients with chronic non-cancer pain are prescribed opioids, and sometimes this has resulted in iatrogenic (from the Greek for “brought forth by the healer”) opioid dependence and subsequent illicit opioid use. The authors of the aforementioned Lancet article write:

“From the 1990s to around 2011, aggressive promotion, underregulation, and overprescribing of pharmaceutical opioids caused a substantial increase in opioid dependence and overdose deaths.”

In fact, in January 2020, the CEO and founder of the pharmaceutical company Insys Therapeutics was convicted of engaging in a racketeering conspiracy to increase the profits from his company’s sublingual fentanyl spray, including the bribing of doctors to prescribe the medication to patients beyond the approved use for cancer pain. He was sentenced to 66 months in prison. Criminal charges against other pharmaceutical executives tied to the opioid epidemic are underway.

It wasn’t until 2010 that rules and regulations were put into place, but unfortunately it was too little too late. Demand stayed high, and the illicit market profited from the mandated decreases in supply. In a sense, we had tasted the forbidden fruit and opened Pandora’s box. Now we can never go back.

The Efficacy of Opioids

The worst part of it is, opioids aren’t even that much better at controlling pain in the first place. In 2018 a systematic review of 96 randomized clinical trials and over 26 000 patients with chronic noncancer pain found that although the use of opioids was associated with less pain and improved physical functioning compared to placebo, the result did not meet the “minimally important difference”, or the smallest amount of improvement in a treatment outcome that patients could recognize as important. The incidence of vomiting, however, was significantly higher in the opioid group.

The 2018 SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial showed that for patients with moderate to severe chronic back pain, or hip or knee osteoarthritis, opioids did not improve pain-related function, and pain intensity was actually better controlled in the nonopioid group (with Tylenol or Advil). Adverse symptoms, however, were significantly more common in the opioid group.

Besides chronic pain, opioids are often prescribed for post-surgical pain. The 2019 PANSAID Randomized Clinical Trial looked at patients after total hip replacement surgery and showed that among the most common nonopioid analgesic regimens, ibuprofen (Advil) alone was the best, and significantly reduced morphine requirements.

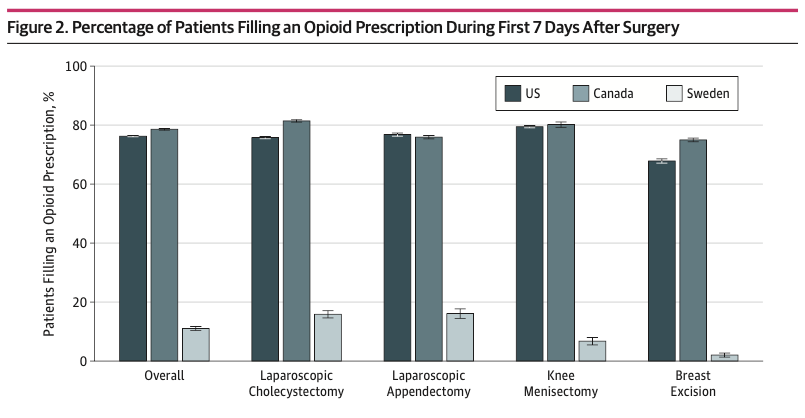

A 2019 cohort study of just under 130 000 patients undergoing the same surgeries in the USA, Canada, and Sweden studied postoperative opioid usage. They found that after surgery in the United States and Canada, patients had a 7-fold higher rate of opioid prescriptions filled than patients in Sweden. Could it be that North Americans felt more pain or had more painful surgeries? No, because the patients shared similar characteristics across the three countries, including age, comorbidities, and type of surgery. While the irresponsible promotion of opioids by pharmaceutical companies play an undeniable role, I believe the discrepancy is also due to our deeper, more systemic cultural relationship to pain that allowed them to propagate their criminal marketing in the first place.

Differences in opioid prescriptions filled after surgery between the three countries. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Ladha et al., 2019.

‘Hacking’ Culture — A Pillar of the American Economy

America has always been an innovator in ‘fast’ things. In other words, immediate gratification. Fast food is a staple of American cuisine with international icons like McDonald’s, Wendy’s, and Kentucky Fried Chicken. The Chinese take-out container was invented in Chicago in the late 19th century. With Amazon Prime Now, customers can get stuff delivered to their door within just 1–2 hours of clicking ‘order’. Americans want things quickly, and they don’t like waiting.

During my undergrad, I was an avid hackathon attendee. Hackathons (a portmanteau of hacking marathon) are typically weekend-long events where computer nerds get together to collaborate intensively on software projects. The culture can loosely be described as sweaty, chaotic, and intense. Sleep and hygiene are quickly sacrificed for the excitement of creating something awesome, and the chance to win some big prizes. Startups often sponsor these events, and it was at a hackathon where I first had a taste of Soylent.

Soylent in different flavors. Photo: Soylent.

Soylent is a meal replacement drink created in 2014 by a Silicon Valley software engineer. It was a fascinating concept: food was a time-consuming hassle that was only necessary for survival, and it could be solved as an engineering problem. Soylent was also cheap ($1.50/meal for the powdered version) and could even be a solution to food insecurity around the world. The idea caught on, and the founders raised $2.1 million via online crowdfunding, and then an additional $1.5 million of private funding right afterward. I bought into this idea too, and I purchased a couple of boxes of Soylent to use during exams when I was busy reviewing (read: cramming) semester-worths of notes to regurgitate them on the exam.

It was great. Meals became a 5-minute affair, the taste was tolerable, I felt full, and I had no dishes to do. However, by the end of the two-week exam period, I felt like I had lost something: the ability to taste, the ability to cook, and the ability to form solid stool.

When Soylent first came out, a big criticism was that in “hacking away” the “tediousness” of cooking and eating, you also hack away the human pleasures that come with preparing food and sharing a meal with others. Food has always been a centerpiece in human social behavior from the dawn of time. When was the last time you willingly hung out with someone in a setting that didn’t involve food or drink? We are so lucky to exist in a time when we have access to all the delicious cuisines on Earth, via both the restaurants that serve us these dishes and the ingredients and online recipes to make them ourselves. Taking that away is like stripping away a bit of makes us human. It’s a similar argument with pain.

Humans and Opioids

Opioids, like all drugs, are useful for a reason — they help us control acute pain, tolerate surgery, and provide symptomatic relief to cancer patients. But they also carry a lot of risks including addiction, dependence, and death.

The Opioid Chapters is a website that features interviews with patients and healthcare workers who have lived experience with opioids. One interviewee injured his back while working as a paramedic, and after trying many treatments, found that opioids were the only drug that dulled his pain. “The opioids worked,” he says. “They are about the only thing that has worked. But my tolerance increased and I needed more. So then it was like, ‘Okay, this is going in the wrong direction.’” At the same time, he is worried that doctors are being pressured to not use opioids at all, even when they are the only thing that works for some patients. Another interviewee talks about waking up one morning to find his wife slumped over, dead from an unintentional fentanyl patch overdose.

Ironically, opioid use may even cause more pain, a phenomenon called “opioid-induced hyperalgesia”. While we don’t fully understand why this happens, scientists believe it has to do with brain neuroplasticity and neurotransmitter modulation upon long-term exposure to opioids. This is another reason why Pandora’s box is next to impossible to close. The longer patients are on chronic opioids, the more likely they are to experience more pain, and consequently need more and more opioids — a never-ending deadly cycle.

Another interviewee, a family doctor, talks about the difficulty that came with taking over a high-opioid-prescriber’s family medicine practice and trying to taper down her patients’ opioid dosages. She reflects on how they got onto the high dosages in the first place and admits that the ‘hacking’ culture spills into medicine as well.

“More and more,” she says, “physicians are being trained to find a pill for every problem, instead of looking at the underlying root causes of disease and actually offering something that is a bit more holistic and durable.”

Dan injured his back working as a paramedic. Opioids are the only thing that dulls his pain, but his tolerance has increased. The Opioid Chapters.

Pain is a Part of Life

I came across an excellent New York Times opinion piece a couple of years ago titled, “After Surgery in Germany, I Wanted Vicodin, Not Herbal Tea”. The author, an American who emigrated to Germany, writes about how she was surprised she was only offered ibuprofen (Advil) for pain control after her hysterectomy (surgical removal of her uterus). She wanted Vicodin (a combination of acetaminophen and hydrocodone, an opioid) instead. The author recalls her anesthesiologist explaining:

“Pain is a part of life. We cannot eliminate it nor do we want to. The pain will guide you. You will know when to rest more; you will know when you are healing. If I give you Vicodin, you will no longer feel the pain, yes, but you will no longer know what your body is telling you. You might overexert yourself because you are no longer feeling the pain signals. All you need is rest. And please be careful with ibuprofen. It’s not good for your kidneys. Only take it if you must. Your body will heal itself with rest.”

If more doctors were brave enough to recommend rest over opioids, and more patients willing to accept it, maybe, just maybe, we might not have had nearly as bad of an opioid crisis.

The opioid crisis was created due to aggressive pharmaceutical marketing, physician greed, and the North American culture of ‘hacking’ away inconveniences such as pain. It has resulted in patient deaths and addictions, a growing illegal trade, and the criminal convictions of pharmaceutical executives. It also resulted in a large discrepancy between the opioid use by Americans compared to use by the rest of the world, despite no good evidence showing opioids are more effective at controlling pain and restoring function compared to non-opioid painkillers.

Technology has come a long way in pushing the frontiers of human possibility. Silicon Valley startups and modern medicine have undoubtedly improved the quality of life for a lot of people. However, as the old saying goes, with great power comes great responsibility, and we should be careful before hacking away the last parts of us that make us who we are.