The Dollar Value of a Human Life

Spoiler…it’s $10 million USD.

I heard a fascinating podcast episode from Planet Money titled “Lives Vs. The Economy” recently, and it blew my mind.

It addressed the question that has been asked more and more recently in the public discourse: “is it ever worth it to shut down the economy to save lives?”, or in other words, “Why can’t we open back up? I need to go back to work! I need a haircut!”.

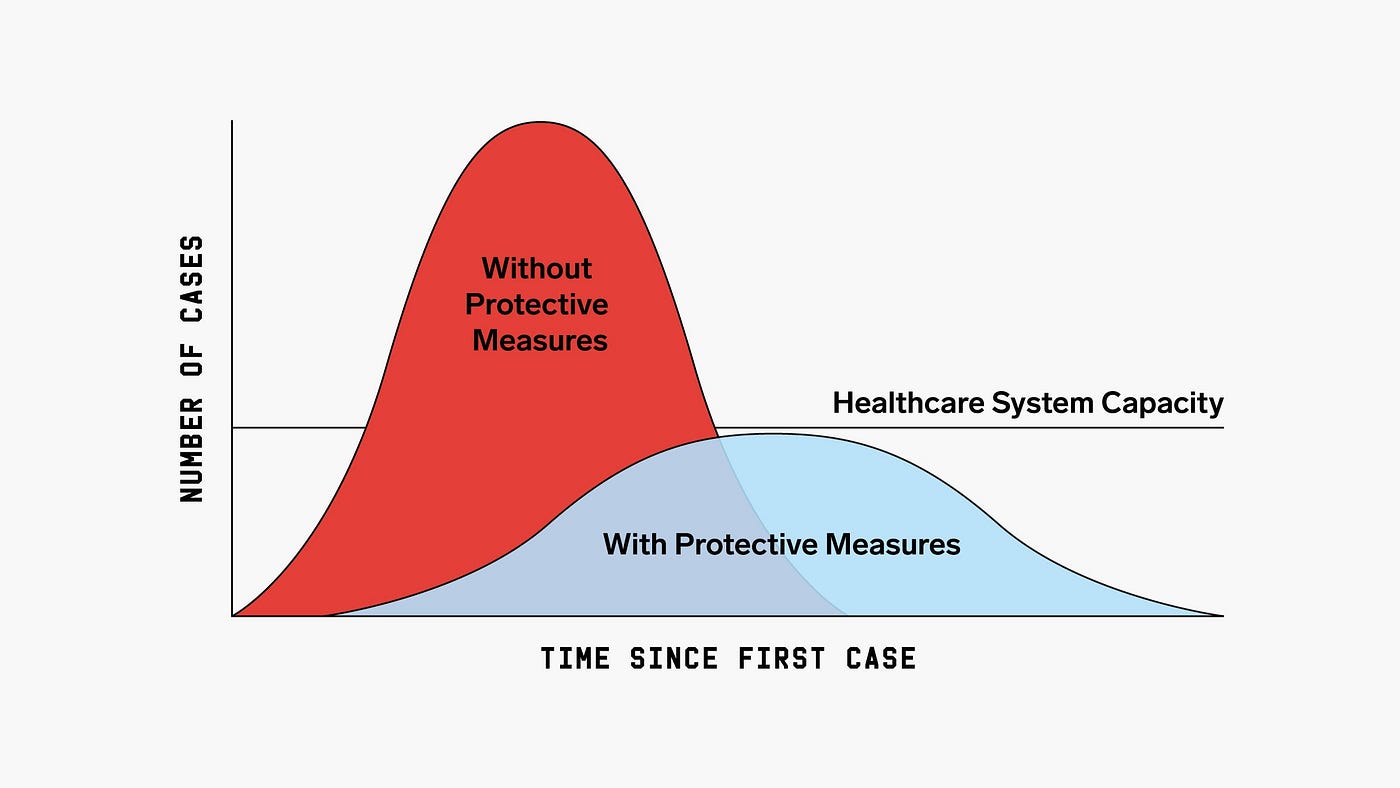

Flattening the curve. WIRED.

On the one hand, it takes nothing short of completely shutting down a country as per public health recommendations in order to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus and “flatten the curve”. Although the area under the curve, or in other words the cumulative total of COVID-19 cases is the same in both scenarios, a situation where a country does nothing to prevent unessential travel and social congregation would result in a situation where the healthcare system is entirely overwhelmed, and many more people would receive suboptimal care and potentially die. As new cases continue to climb day by day, yes, we definitely need to continue to physically distance and continue stay-at-home orders. Just because things are starting to look like they are getting better, doesn’t mean things are completely better. In fact, the most common reason patients stop taking their depression or anxiety medication, and then consequently become depressed and anxious again, is because they start to feel better! Going to social gatherings now would be irresponsible to the health of the greater society, and the healthcare workers putting their lives on the line for you. As members of a society, we have to sacrifice some personal freedoms when the benefit to society as a whole is so much bigger.

The emergency department team at Vancouver Coastal Health. (Photo: Vancouver Coastal Health / Facebook)

On the other hand, you simply can’t ignore the fact that the economy is devastated, globally, right now. Many businesses have shut down entirely for the foreseeable future, and the International Labour Organization predicts the loss of 195 million full-time jobs in the next three months. Unemployment numbers have skyrocketed, and although governments are doing their best to support citizens with financial stimulus packages, many who have been laid off are struggling to pay their bills and continue to provide for their family. It makes complete sense why people are worried at how much longer the lockdowns are going to be, when they have their livelihoods taken away. The haircut thing, though, not so much. Simply put, the economy cannot stay shut down forever, and we can’t shut it down at any cost—for example, we could die of starvation.

Both sides have valid arguments. So what do we do in the face of a difficult decision with different risks and benefits? We turn to the beautiful field of economics.

In its most simple and concise definition, economics is the study of how an agent (society, business, or person) uses its limited resources. Ever since I came across Freakonomics (book, and then podcast) I was hooked by the concept of uniting math and data with real-world implementation and policy changes. The amazing thing about economics is that it can be as abstract as a complex model of the macro economy, but it can also be as practical as showing up in your everyday life. Every single person needs to make so many decisions everyday, as to what to do with our own limited resources—time and energy. Economics can help us put a framework to these decisions and make issues which are sometimes emotional, seemingly impossible to rationalize, into an objective recommendation.

Anyway, back to the issue at hand. In order to answer the question of “is it worth it to shut down the economy to save lives?”, we need to know the value of a human life. Yes, it’s a difficult and extremely uncomfortable question to ask, but not one which is unfamiliar to economists.

“The people who say how could you put a value on life, I say, how could you not? How could you pretend people are valueless? What would it mean to think of people having infinite value? We’d spend all of our resources on saving one person, people wouldn’t make that decision.” — economist Dr. Betsy Stevenson, University of Michigan.

Economists are the ones who need to decide how much compensation to give to families of victims of tragedies like shootings or terrorist acts. What an extremely uncomfortable position to be in. The 9/11 fund was a little bit different because it was tied to protecting airlines and the World Trade Center from litigation, so I won’t get into that. But a fascinating listen if you are interested.

In the case of COVID-19, we are referring more so to the “statistical value of life”, which federal agencies use in their calculations to make decisions all the time. Up until the 80s, it used to be based on the “cost of death”, both the medical cost as well as the amount of income lost to survivors. This is often used in wrongful death lawsuits, and this value was $300,000 in 1982. However, this changed when the issue of marking hazardous materials (WHMIS as we know in Canada today) was brought up to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in the United States. It’s crazy to think now, but at one point companies were not mandated to use labels to warn workers of substances such as asbestos, corrosive and flammable chemicals. The fallibility of the cost of death model came to light when the cost of printing labels, which was estimated to be around $2.6 billion, was actually more than the value of lives potentially saved. People thought, that can’t possibly be right, and appealed.

WHMIS safety labels. Source: https://www.vocamtraining.ca/what-is-whmis-all-about/

That’s when the economist W. Kip Viscusi came into the picture. In order to come up with a more accurate number of the value of life, he came up with the ingenious idea of looking how much society compensates workers who take on extra risks (such as construction workers, firefighters, and now frontline healthcare workers). “How much is society willing to pay to prevent the risk of one expected death?” The answer? Around $10 million dollars (today), irregardless of age, race, class, gender, education, and income. It’s genius because it is actually based on the value we ourselves (as a society) have implicitly assigned to our own lives, based on the amount of money workers require in exchange for agreeing to taking on extra risk. And with that new value, hazardous workplace materials across the country were finally labelled. Many other safety regulations followed.

So in the context of COVID-19, taking the low estimate of the potential number of lives that could be saved by shutting down the economy to be roughly 1 million:

1 million lives saved x $10 million per statistical life = $10 trillion USD

…which is around half of the US gross domestic product. Not accounting for the medical costs of disease, and the fact that opening up the economy in a pandemic wouldn’t mean businesses would operate at 100%, it still makes complete objective sense to not re-open the economy now.

But there is a tough decision ahead. The government will open up the economy at some point, even when things aren’t entirely safe. As Dr. Stevenson said at the end of the podcast: “We can’t just close the economy until there are zero deaths. We don’t do that now.”

Most of us would say our lives are “priceless” to us. Yet most of us would also not be willing to pay an infinite amount for a safer car that could potentially prevent death. In medicine, risk/benefit ratios are calculated all the time by clinicians when suggesting treatment plans for patients, that directly affect their risk of dying. This is why evidence-based clinical research is so important to guide clinical decision making, and why statistics like the “number needed to treat (NNT)” or the “number needed to harm (NNH)” are used, and the importance of the concept of “Choosing Wisely” for not performing unnecessary screening tests on healthy patients. These (including the $10 million value of a statistical life) are by no means perfect and can change. The alternative however, to not have any explicit discussion or thought about the risks or benefits, and therefore the value of our decisions, would still involve implicit and unknown valuation, which would be clearly less ideal overall.

In conclusion, economics can be a great way to rationalize decision-making from whether to go on a run or whether to test someone for breast cancer. Risks and benefits must always be balanced, and shutting down the economy in the context of a pandemic is no exception. And currently, all the evidence is begging you to please stay at home. We understand your frustration, and we will get through this together.