COVID-19 and Climate Change

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes… but there are pretty pictures!

I attended an online webinar the other day organized by the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment (CAPE). The session was titled “COVID-19 and climate change - Where do we go from here?” and consisted of a panel of speakers, including physicians and other board members of the organization. I was interested because I had heard something about carbon emissions dropping ever since people have been staying home and the economy had been slowing down. I wouldn’t say I have a passion for the environment, but I care about climate change and what inaction could mean for the Earth we are inheriting from our parents and the Earth we are leaving behind for our children. There are also many health implications. I heard this phrase once, “there are no healthy people on a dying planet”.

I wanted to share some of my takeaways from the event. The thing that I think is most effective at conveying the impact of climate change is data, and elegant associations made from that data. But maybe that’s just me.

Exhibit A - COVID-19 and energy use

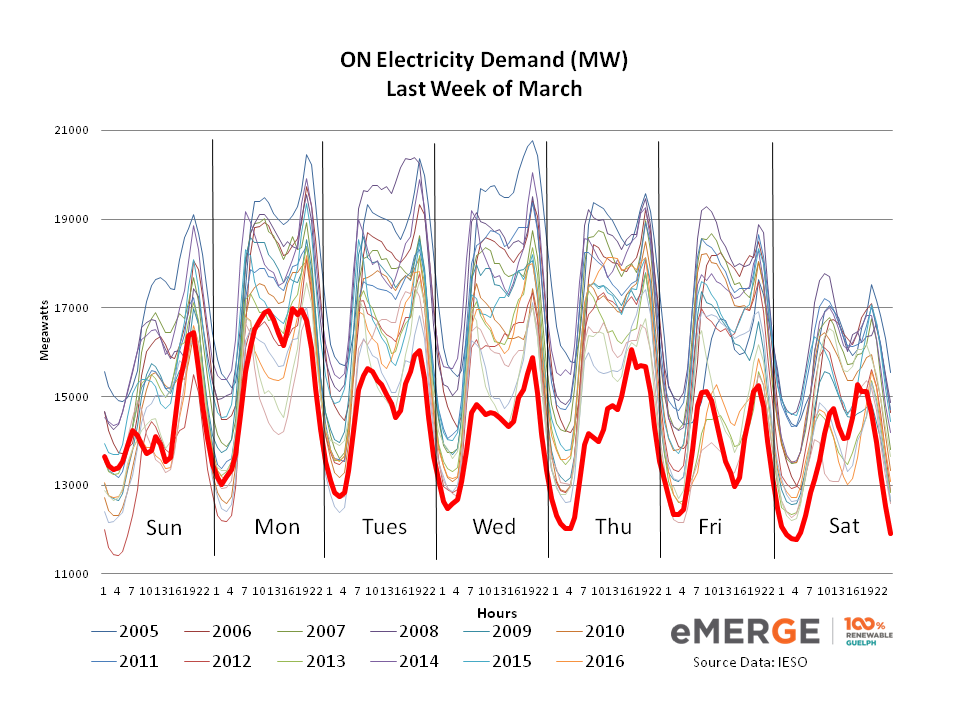

An environmental consulting organization from Guelph called eMERGE put together some interesting data. They plotted Ontario’s hourly electricity demand for the last week of March, and compared it with the usage data during the same week during the years 2005-2016. It’s fascinating to see how the usage is fairly consistent at the start of the week, but then drops in anticipation and following the closure of all non-essential workplaces in Ontario by Wednesday March 25.

Source: https://emergeguelph.ca/how-our-hydro-footprint-is-changing-in-a-covid-19-world/

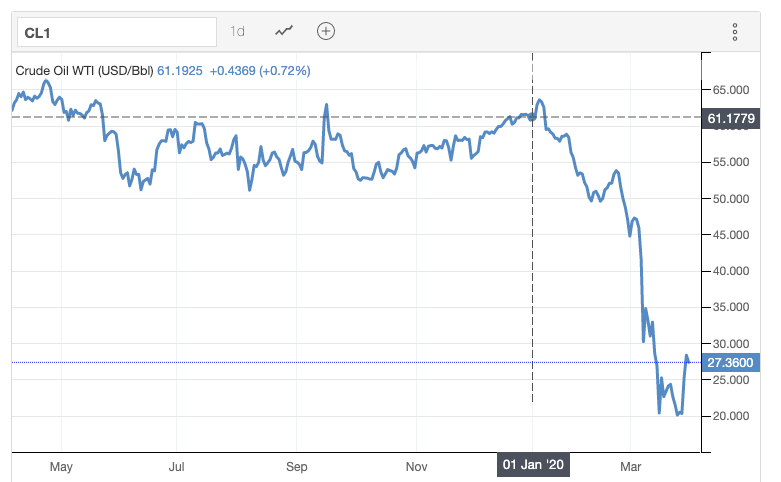

Another thing you’ve probably noticed are the unbelievablely low gas prices. Oil hasn’t been this cheap since the early 2000s! Besides the small fact that people aren’t driving to work anymore, this is also superimposed on top of a price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, who are both increasing their crude oil production since an OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) deal to lower output had expired at the end of March. This has crippled the oil markets, with the price of oil plummeting more than 50% since Jan 2020.

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/crude-oil as of April 6, 2020 09:53AM

Exhibit B: The Research – who would’ve thought, nature is good for you!

Dr. Melissa Lem, a family doctor in Vancouver as well as a CAPE board member, highlighted four scientific papers that looked at the intersection of nature and health. She is also the Director of Parks Prescriptions for the BC Parks Foundation, which could explain the articles that she chose to share.

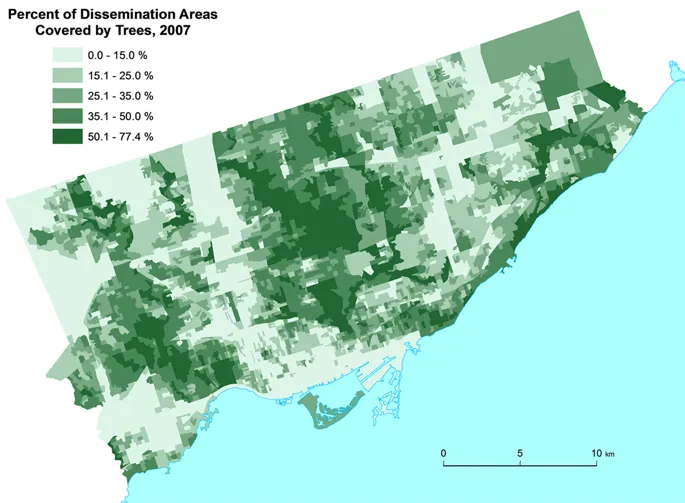

The first one was published by Kardan et al. in 2015 in the Nature’s Scientific Reports journal. It’s called “Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center”, and basically they used satellite imagery and questionnaire-based self reports to see if there was any correlation between the density of trees of where someone lived in the city of Toronto with their general health. They found that “having 10 more trees in a city block, on average, improves health perception in ways comparable to an increase in annual personal income of $10,000 and moving to a neighborhood with $10,000 higher median income or being 7 years younger”. They also found that “having 11 more trees in a city block, on average, decreases cardio-metabolic conditions in ways comparable to an increase in annual personal income of $20,000 and moving to a neighborhood with $20,000 higher median income or being 1.4 years younger.” Wow. And cardio-metabolic conditions by the way includes hypertension, high blood glucose, obesity (both overweight and obese), high cholesterol, myocardiac infarction, heart disease, stroke and diabetes. Interestingly, there was no significant difference found with mental health problems including depression, anxiety, and addiction.

Side note: I was wondering why they chose to look at the perception of health as an outcome, and here’s what they say: “Subjective self-rated health perception was chosen as one of the health outcomes because self-perception of health has been found to be related to morbidity and mortality rates and is a strong predictor of health status and outcomes in both clinical and community settings”. Interesting! I can’t say I understand the math behind how they got those exact numbers for income and age, but they are powerful, objective measures!

Data was constructed from Geographical Information System (GIS) polygon data set ‘Forest and Land Cover’, which from a Google search is simply available here. Cool!

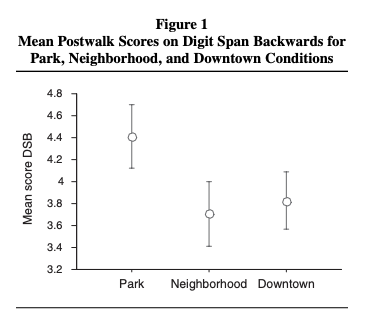

The second study Dr. Lem mentioned was done by Taylor & Kuo in 2008, published in the Journal of Attention Disorders. The study was called “Children With Attention Deficits Concentrate Better After Walk in the Park”, and the result is right there in the title. They enrolled 17 children aged 7 to 12 years old who are clinically diagnosed with ADHD and had them go through 3 guided 20-minute walks through a city park, downtown, or residential area. The walks were 1 week apart, and children were randomized to the order of walks. After each walk, concentration was measured using the Digit Span Backwards test (repeating lists of numbers backwards). The result? They found that the children with ADHD had the highest concentration after the walk in the park, and the effect size was comparable to those reported for the ADHD medication methylphenidate, otherwise known as Ritalin!

DSB = Digit Span Backwards test

Ok big deal, outcomes like perception of health and concentration are prone to confounding factors and subjectivity. I want cold, hard indisputable evidence. Well, the next study proved just that.

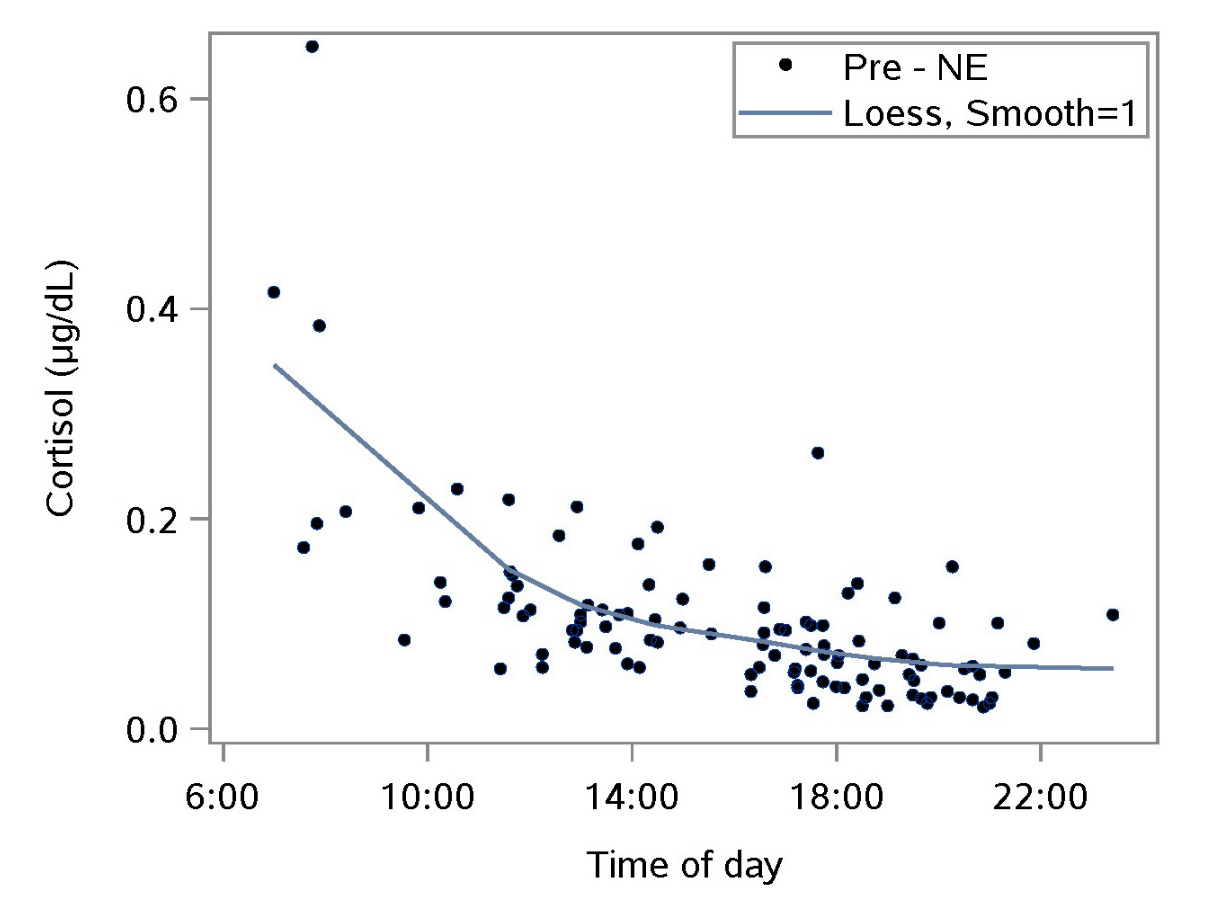

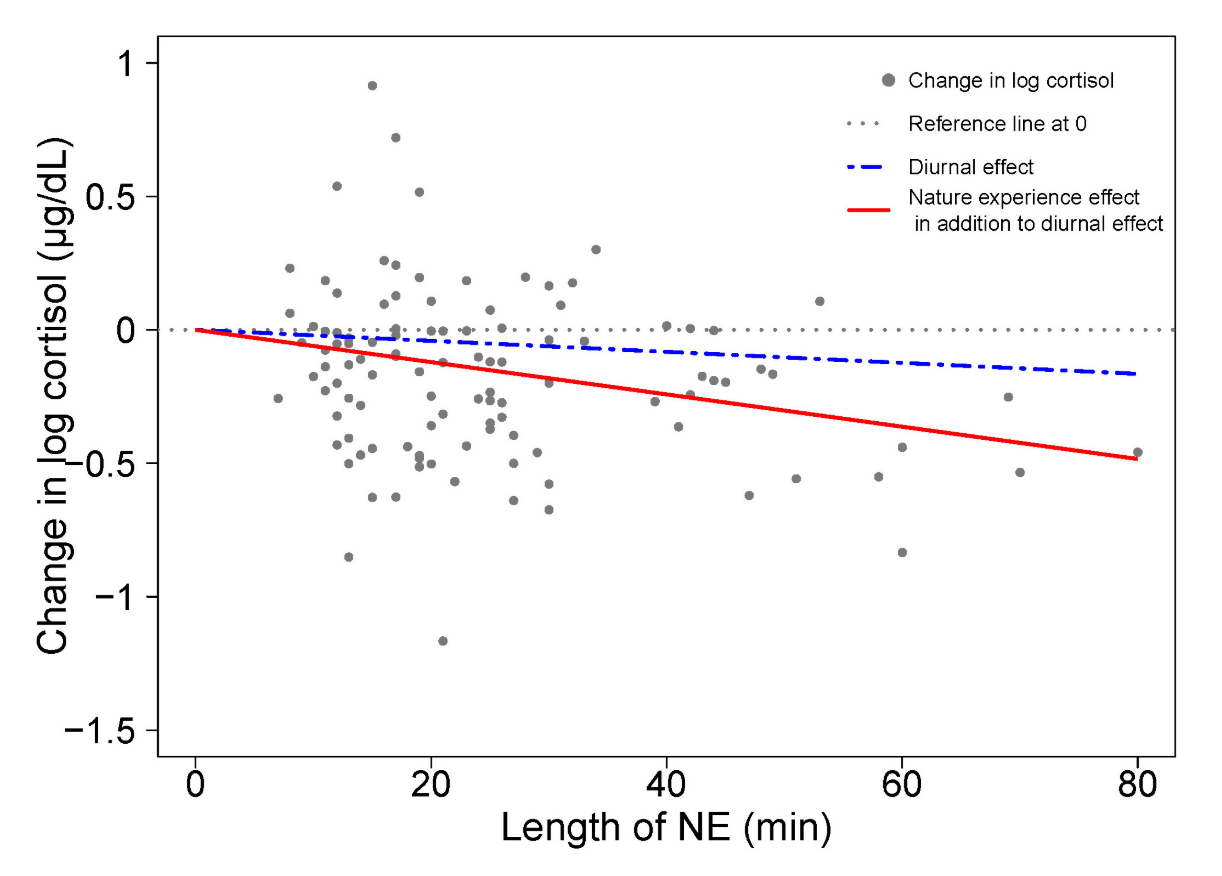

In their 2019 paper, “Urban nature experiences reduce stress in the context of daily life based on salivary biomarkers”, Hunter et al. looked at two physiological biomarkers of stress—salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase, before and after spending at least 10 minutes outdoors in nature (“a nature experience”). This can be done any time throughout the day, at the participants’ discretion. As they write in their introduction, the researchers’ ultimate goal was to come up with a “nature prescription” as a preventative, self-administered, low-cost treatment for mental well-being. As with any medication, the effectiveness of “nature pills” need to be validated for their clinical pharmacology and dose-response. Sometimes this can be nuanced, for example, cortisol release follows a diurnal (daily) pattern. Due to a phenomenon called the cortisol awakening response, salivary cortisol levels are highest in the morning around half an hour after awakening, and then drop off during the day. Cortisol is produced by the adrenal cortex and regulated by the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (brain feedback pathway), however the cortisol awakening response is controlled by the hippocampus, which takes over the HPA axis. The theory behind this increase in cortisol is thought to have to do with the hippocampus “preparing” the body for the stresses of the day. Interestingly, this response is reversed in people who work night shifts. It does not seem to occur with naps and seems to be elevated in people of lower socioeconomic status. A similar phenomenon occurs with alpha amylase, the other stress marker the study looked at, which is a digestive enzyme secreted by the pancreas and salivary gland, to pre-digest starches into sugars in your mouth. However, alpha amylase undergoes a diurnal rise rather than a drop.

Anyway, because of these phenomena, which is different for each individual, the researchers needed to separate the effect of the nature pill from the diurnal cycles in cortisol and amylase (which are relatively stable for each individual). Instead of taking multiple saliva samples throughout the day to establish individual patient baselines, they were able to extrapolate the diurnal trajectory based on pre-nature pill samples and accommodating for time of day (I have to admit, I don’t fully understand this part). And the results? They found that a single “nature experience” (of 10 minutes or more) reduced salivary cortisol by 21%/h and reduced salivary amylase by 28%/h. The optimal “dose”? 20-30 minutes. That’s all it takes, half an hour of being outside! A quick walk around the block, or even as part of your commute.

NE = nature experience

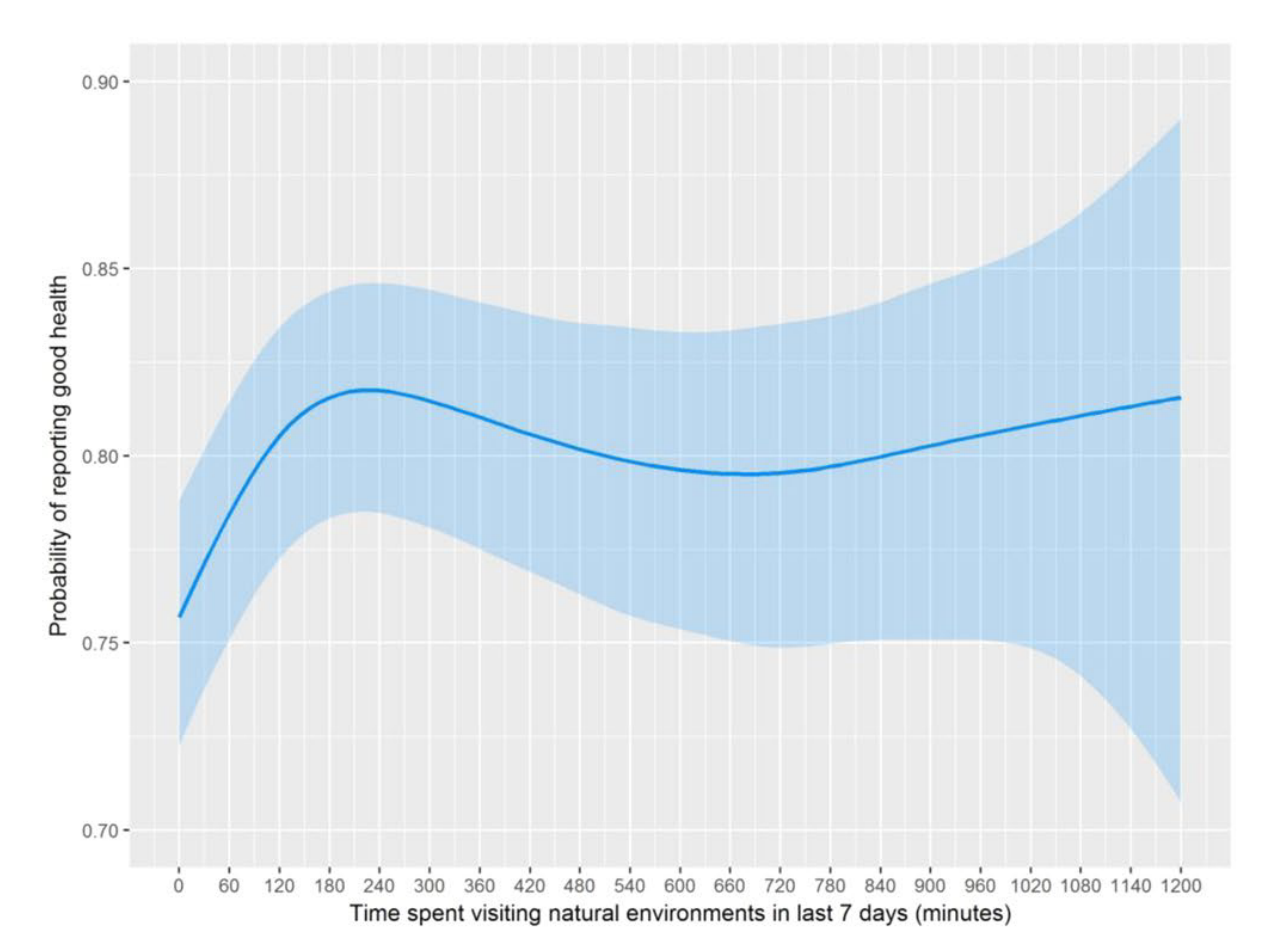

And finally, the last paper was another Nature Scientific Reports article written by White et al. in 2019, entitled “Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing”. Couldn’t get clearer than that. They took the survey responses of just under 20000 people in the UK and looked at relationships between weekly recreational nature contact (defined as contact with parks, woodlands, and beaches) and self-reported health and well-being. They controlled for confounders such as residential greenspace (which we know has a positive effect, from paper #1!). The results? Compared to no nature contact in the past week, people who had at least 120 minutes (2 hours) of nature contact were 1.6 times as likely to report better health, and 1.2 times as likely to report higher well-being. And as we know from study #1, self-perception of health has a strong correlation to actual morbidity and mortality, as well as health status. Positive associations peaked between 200-300 minutes per week, with (interestingly) no further gain. The pattern was consistent across people of older age and with chronic health conditions. Another key finding was that it didn’t matter how the 120 minutes was achieved, whether in one sitting (ironic phrase), or spread out across the week.

TL;DR. So what does this all mean?

- More greenspace in your neighbourhood = more health, wealth, and youth.

- A 20min walk in a city park had the same effect as Ritalin for children with ADHD.

- A 20-30min “nature experience” optimally drops the biomarkers in your saliva associated with stress.

- 2-5 hours of nature contact per week = better health. Doesn’t matter how you do it.

Humans evolved and adapted to living in nature, not the concrete jungle. Nature is better for your health.

Exhibit C — The idea of “Planetary Health”

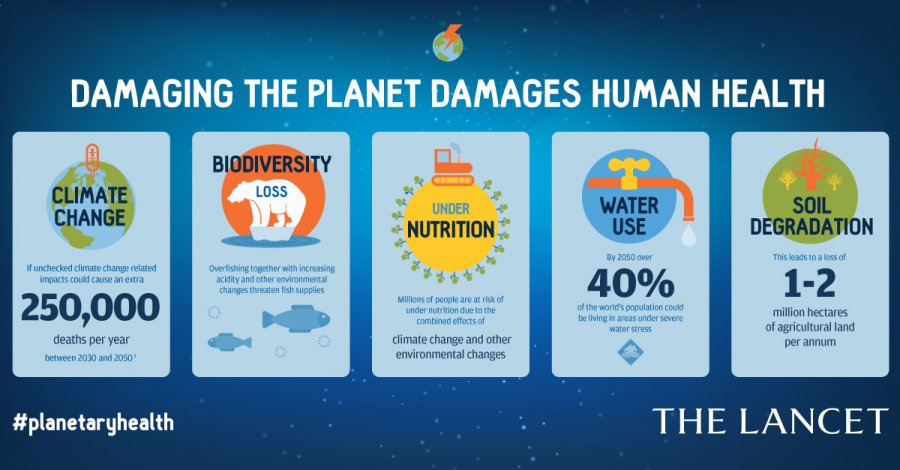

Dr. Courtney Hayward is an ER doctor in Yellowknife, NWT, as well as the CAPE board president. She talked about the concept of “Planetary Health”, how our health care system can only function when it is built on a foundation of natural systems (oxygen, water, food, climate) and socioeconomic factors (job security, shelter, education), which are determinants of health. The quote from above still rings true: there are no healthy people on a dying planet.

In 2015 the Rockefeller Foundation and the Lancet medical journal formed a commission and wrote a report. I’m just going to copy and paste the executive summary because I think it is just fantastically written:

By almost any measure, human health is better now than at any time in history. Life expectancy has soared from 47 years in 1950–1955, to 69 years in 2005–2010, and death rates in children younger than 5 years of age have decreased substantially, from 214 per thousand live births in 1950–1955, to 59 in 2005–2010. But these gains in human health have come at a high price: the degradation of nature’s ecological systems on a scale never seen in human history. A growing body of evidence shows that the health of humanity is intrinsically linked to the health of the environment, but by its actions humanity now threatens to destabilise the Earth’s key life-support systems.

As a Commission, we conclude that the continuing degradation of natural systems threatens to reverse the health gains seen over the last century. In short, we have mortgaged the health of future generations to realise economic and development gains in the present.

“We have mortgaged the health of future generations to realise economic and development gains in the present.” Wow.

Full infographic: https://www.thelancet.com/infographics/planetary-health

Conclusions

- The current pandemic is greatly affecting the way we use energy.

- Research clearly shows positive health effects of nature.

- Human health is very much integrated and dependent on environmental health. If we care about human health, then we must care about the health of the environment as well.

One of the stated goals of the webinar was “How can we talk about climate change during a global pandemic without seeming tone deaf or opportunistic?”. I don’t know the answer to that. I can say I care about the environment as much as I want without doing anything. Hopefully, this summary and the links help to increase awareness—I know writing it has taught me a lot. But I’ll end with a quote from Dr. Hayward near the end of the Q and A session, regarding the zoonotic transmission of the novel coronavirus:

COVID-19 is exactly an example of why we need to care about the interface between human society and nature.

Addendum (April 14). Some of my classmates sent me some additional articles related to COVID and climate change. I didn’t go through them in detail, but here they are with a one-liner:

- Exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States.. This is a neat study from Harvard that looked at pollution data (measured in average PM2.5 levels, which is basically a measure of fine particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 microns) and the COVID-19 death rate across the country. They fonud that an increase of 1 ug/m^3 in PM2.5 level is associated with a 15% increase in the COVID-19 death rate. You can’t get a more direct connection than that.

- Positive Effects of Nature on Cognitive Performance. Another use of the backwards digit span task, this time as a measure of cognition in general, and in adults. Results showed significant beneficial effects of nature compared to urban environments. Awesome.